Giving Medicine to Children

The following web sites had useful information regarding giving medicine to children:

http://www.fda.gov/FDAC/features/196_kid.htmlThe web site of the U.S. government agency Food and Drug Administration

http://www.robynsnest.com/givingmed.htm

http://pediatrics.about.com/od/childhoodmedications/Pharmacology_and_Childhood_Medications.htm http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/give-medicine-children

http://familydoctor.org/online/famdocen/home/children/parents/safety/097.html

http://www.chw.org/display/PPF/DocID/33277/Nav/1/router.asp

http://www.familyeducation.com/article/0,1120,1-7958,00.html

http://www.chpa-info.org/ChpaPortal/ForConsumers/SpotlightOnConsumerHealth/GivingMedicinetoChildren/

The article below originally appeared in the January-February 1996 FDA Consumer.The version below is from a reprint of the original article and contains revisions made in May 1996.The version below has been edited.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How to Give Medicine to Children by Rebecca D. Williams"Open wide ... here comes the choo-choo."

When it comes to giving children medicine, a little imagination never hurts.

But what's more important is vigilance: giving the medicine at the right time at the right dose, avoiding interactions between drugs, watching out for tampering, and asking your child's doctor or the pharmacist about any concerns you may have.

Whether it's a prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drug, dispensing medicine properly to children is important. Given incorrectly, drugs may be ineffective or harmful.

Read the Label

"The most important thing for parents is to know what the drug is, how to use it, and what reactions to look for," says Paula Botstein, M.D., pediatrician and acting director of the Food and Drug Administration's Office of Drug Evaluation III. She recommends that a parent should ask the doctor or pharmacist a number of questions before accepting any prescription:

What is the drug and what is it for? Will there be a problem with other drugs my child is taking? How often and for how long does my child need to take it? What if my child misses a dose? What side effects does it have and how soon will it start working?

It's also a good idea to check the prescription after it has been filled. Does it look right? Is it the color and size you were expecting? If not, ask the pharmacist to explain.Check for signs of tampering in any OTC product. The safety seal should be intact before opening. Also, parents should be extra careful to read the label of over-the-counter medicines.

"Read the label, and read it thoroughly," says Debra Bowen, M.D., an internist and director of FDA's medical review staff in the Office of OTC Drugs. "There are many warnings on there, and they were written for a reason. Don't use the product until you understand what's on the label."

Make sure the drug is safe for children. This information will be on the label. If the label doesn't contain a pediatric dose, don't assume it's safe for anyone under 12 years old. If you still have questions, ask the doctor or pharmacist.

Children are more sensitive than adults to many drugs. Antihistamines and alcohol, for example, two common ingredients in cold medications, can have adverse effects on young patients, causing excitability or excessive drowsiness. Some drugs, like aspirin, can cause serious illness or even death in children with chickenpox or flu symptoms. Both alcohol and aspirin are present in some children's medications and are listed on the labels.

Younger and Trickier

The younger the child, the trickier using medicine is. Children under 2 years shouldn't be given any over-the-counter drug without a doctor's OK. Your pediatrician can tell you how much of a common drug, like acetaminophen (Tylenol), is safe for babies.

Prescription drugs, also, can work differently in children than adults. Some barbiturates, for example, which make adults feel sluggish, will make a child hyperactive. Amphetamines, which stimulate adults, can calm children.

When giving any drug to a child, watch closely for side effects.

"If you're not happy with what's happening with your child, don't assume that everything's OK," says Botstein. "Always be suspicious. It's better to make the extra calls to the doctor or nurse practitioner than to have a bad reaction to a drug."

And before parents dole out OTC drugs, they should consider whether they're truly necessary, Botstein says.

Americans love to medicate--perhaps too much. A study published in the October 1994 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association found that more than half of all mothers surveyed had given their 3-year-olds an OTC medication in the previous month.

Not every cold needs medicine. Common viruses run their course in seven to 10 days with or without medication. While some OTC medications can sometimes make children more comfortable and help them eat and rest better, others may trigger allergic reactions or changes for the worse in sleeping, eating and behavior. Antibiotics, available by prescription, don't work at all on cold viruses.

"There's not a medicine to cure everything or to make every symptom go away," says Botstein. "Just because your child is miserable and your heart aches to see her that way, doesn't mean she needs drugs."

Dosing Dilemmas

The first rule of safety for any medicine is to give the right dose at the right time interval.

Prescription drugs come with precise instructions from the doctor, and parents should follow them carefully. OTC drugs also have dosing instruction on their labels. Getting the dosage right for an OTC drug is just as important as it is for a prescription drug.

Reactions and overdosing can happen with OTC products, especially if parents don't understand the label or fail to measure the medicine correctly. Similar problems can also occur when parents give children several different kinds of medicine with duplicate ingredients.

"People should exercise some caution about taking a bunch of medicines and loading them onto a kid," Botstein says.

Pediatric liquid medicines can be given with a variety of dosing instruments: plastic medicine cups, hypodermic syringes without needles, oral syringes, oral droppers, and cylindrical dosing spoons.

Whether they measure teaspoons, tablespoons, ounces, or milliliters, these devices are preferable to using regular tableware to give medicines because one type of teaspoon may be twice the size of another. If a product comes with a particular measuring device, it's best to use it instead of a device from another product.

It's also important to read measuring instruments carefully. The numbers on the sides of the dosing instruments are sometimes small and difficult to read. In at least one case, they were inaccurate. In 1992, FDA received a report of a child who had been given two tablespoons of acetaminophen rather than two teaspoons because the cup had confusing measurements printed on it. The incident prompted a nationwide recall of medicines with dosage cups.

The following are some tips for using common dosing instruments:

Syringes: Syringes are convenient for infants who can't drink from a cup. A parent can squirt the medicine in the back of the child's mouth where it's less likely to spill out. Syringes are also convenient for storing a dose. The parent can measure it out for a babysitter to use later. Some syringes come with caps to prevent medicine from leaking out. These caps are usually small and are choking hazards. Parents who provide a syringe with a cap to a babysitter for later use should caution the sitter to remove the cap before giving the medicine to the child. The cap should be discarded or placed where the child can't get at it. There are two kinds of syringes: oral syringes made specifically for administering medicine by mouth, and hypodermic syringes (for injections), which can be used for oral medication if the needles are removed. For safety, parents should remove the needle from a hypodermic syringe.Always remove the cap before administering the medication into the child's mouth. A standard hypodermic syringe has a protective plastic cap on. When in place, the cap appears to be an integral, yet inconspicuous, part of the syringe.

The syringe can be loaded with cap in place: The plastic cap is simply intended to be a protective barrier to the syringe's nozzle.Figure A liquid medication can be drawn up into a hypodermic syringe without removing the cap. Liquid can easily enter the syringe nozzle through clearance around the cap. Liquid medication can be poured into the barrel of the syringe after removing the plunger, with the cap still in place. In either case, the potential exists for administering liquid medication without first removing the cap.

Potential hazard of using capped syringe when administering liquid medication:

If left on a loaded hypodermic syringe, the cap could pop off in the child's mouth and could choke the child. FDA is working with manufacturers to eliminate the safety hazards posed by the caps. Until then, parents must be extra cautious when using capped syringes.

Always remove the cap before administering the medicine. Throw it away or place it out of the reach of children.

Droppers: These are safe and easy to use with infants and children too young to drink from a cup. Be sure to measure at eye level and administer quickly, because droppers tend to drip.

Cylindrical dosing spoons: These are convenient for children who can drink from a cup but are likely to spill. The spoon looks like a test tube with a spoon formed at the top end. Small children can hold the long handle easily, and the small spoon fits easily in their mouths.

Dosage cups: These are convenient for children who can drink from a cup without spilling. Be sure to check the numbers carefully on the side, and measure out liquid medicine with the cup at eye level on a flat surface.

FDA Proposes New RegulationsFDA is working on changing the labels of over-the-counter medications to make them more eye-catching, easier to read, and consumer-friendly. One such label appears on the recently approved OTC version of children's Motrin.

For prescription drugs, FDA took measures in December 1994 to provide more information to health-care providers about use of those products in children. This rule was final in January 1995.

The agency now lets prescription drug manufacturers base pediatric labeling on data extrapolated from adequate and well-controlled adult studies, together with other information about safety and dosing in children. This is allowed as long as the agency concludes that the course of the disease and the drug's effects are sufficiently similar in children and adults.

Presently, most prescription drugs do not contain pediatric doses on their labels. A 1979 regulation required full clinical trials in children as the basis for pediatric labeling. Doctors who need to prescribe those drugs to children do so based on their own experience and reports in medical literature. The new regulations will give health-care providers more information to prescribe medicine for children safely.

In addition, FDA is taking steps to increase the numbers of drugs being tested in children, and the agency is working closely with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to conduct pediatric studies.

The goal of FDA's changes is to help ensure that whenever a child receives medication, it is as safe and effective as possible.

Rebecca D. Williams is a writer in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

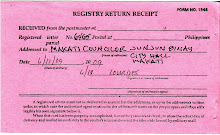

image of registry return receipt of letter addressed to Makati councilor J. J. Binay

No comments:

Post a Comment