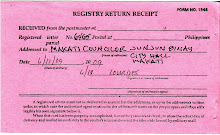

Advisory re Bangus restaurant at unit 127-128 North Arcade, SM Mall of Asia, Pasay City. I sent

a request to said restaurant for information about said restaurant. Based on evidence, said

request for information was received by said restaurant's agent. Said restaurant has not

provided the requested information.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

An Introduction to Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms (in most cases, bacteria) that are similar to

beneficial microorganisms found in the human gut. They are also called

“friendly bacteria” or “good bacteria.” Probiotics are available to consumers

mainly in the form of dietary supplements and foods. They can be used as

complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).1

Key Points

• People use probiotic products as CAM to prevent and treat certain illnesses

and support general wellness.

• There is limited evidence supporting some uses of probiotics. Much more

scientific knowledge is needed about probiotics, including about their safety

and appropriate use.

• Effects found from one species or strain of probiotics do not necessarily

hold true for others, or even for different preparations of the same species

or strain.

• Tell your health care providers about any CAM practices you use. Give them

a full picture of what you do to manage your health. This will help ensure

coordinated and safe care. For tips for talking with your health care

providers about CAM, see NCCAM’s Time to Talk campaign at

nccam.nih.gov/timetotalk/.

What Probiotics Are

Experts have debated how to define probiotics. One widely used definition,

developed by the World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations, is that probiotics are “live microorganisms,

which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the

host.” (Microorganisms are tiny living organisms—such as bacteria, viruses, and

yeasts—that can be seen only under a microscope.)

1

CAM is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not

presently considered to be part of conventional medicine. Complementary medicine is used

together with conventional medicine, and alternative medicine is used in place of conventional

medicine. Some health care providers practice both CAM and conventional medicine.

Probiotics are not the same thing as prebiotics—nondigestible food ingredients that selectively

stimulate the growth and/or activity of beneficial microorganisms already in people’s colons.

When probiotics and prebiotics are mixed together, they form a synbiotic.

Probiotics are available in foods and dietary supplements (for example, capsules, tablets,

and powders) and in some other forms as well. Examples of foods containing probiotics

are yogurt, fermented and unfermented milk, miso, tempeh, and some juices and soy

beverages. In probiotic foods and supplements, the bacteria may have been present

originally or added during preparation.

Most probiotics are bacteria similar to those naturally found in people’s guts, especially

in those of breastfed infants (who have natural protection against many diseases). Most

often, the bacteria come from two groups, Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium. Within each

group, there are different species (for example, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium

bifidus), and within each species, different strains (or varieties). A few common

probiotics, such as Saccharomyces boulardii, are yeasts, which are different from bacteria.

Some probiotic foods date back to ancient times, such as fermented foods and cultured

milk products. Interest in probiotics in general has been growing; Americans’ spending

on probiotic supplements, for example, nearly tripled from 1994 to 2003.

Uses for Health Purposes

There are several reasons that people are interested in probiotics for health purposes.

First, the world is full of microorganisms (including bacteria), and so are people’s bodies—in

and on the skin, in the gut, and in other orifices. Friendly bacteria are vital to proper

development of the immune system, to protection against microorganisms that could cause

disease, and to the digestion and absorption of food and nutrients. Each person’s mix of

bacteria varies. Interactions between a person and the microorganisms in his body, and among

the microorganisms themselves, can be crucial to the person’s health and well-being.

This bacterial “balancing act” can be thrown off in two major ways:

1. By antibiotics, when they kill friendly bacteria in the gut along with unfriendly bacteria.

Some people use probiotics to try to offset side effects from antibiotics like gas, cramping,

or diarrhea. Similarly, some use them to ease symptoms of lactose intolerance—a

condition in which the gut lacks the enzyme needed to digest significant amounts of the

major sugar in milk, and which also causes gastrointestinal symptoms.

2. “Unfriendly” microorganisms such as disease-causing bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and

parasites can also upset the balance. Researchers are exploring whether probiotics could

halt these unfriendly agents in the first place and/or suppress their growth and activity in

conditions like:

• Infectious diarrhea

• Irritable bowel syndrome

NCCAM-2

----------------------- Page 3-----------------------

• Inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease)

• Infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a bacterium that causes most ulcers and

many types of chronic stomach inflammation

• Tooth decay and periodontal disease

• Vaginal infections

• Stomach and respiratory infections that children acquire in daycare

• Skin infections.

Another part of the interest in probiotics stems from the fact there are cells in the digestive

tract connected with the immune system. One theory is that if you alter the microorganisms in

a person’s intestinal tract (as by introducing probiotic bacteria), you can affect the immune

system’s defenses.

What the Science Says

Scientific understanding of probiotics and their potential for preventing and treating health

conditions is at an early stage, but moving ahead. In November 2005, a conference that was

cofunded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) and

convened by the American Society for Microbiology explored this topic.

According to the conference report, some uses of probiotics for which there is some

encouraging evidence from the study of specific probiotic formulations are as follows:

• To treat diarrhea (this is the strongest area of evidence, especially for diarrhea from rotavirus)

• To prevent and treat infections of the urinary tract or female genital tract

• To treat irritable bowel syndrome

• To reduce recurrence of bladder cancer

• To shorten how long an intestinal infection lasts that is caused by a bacterium called

Clostridium difficile

• To prevent and treat pouchitis (a condition that can follow surgery to remove the colon)

• To prevent and manage atopic dermatitis (eczema) in children.

The conference panel also noted that in studies of probiotics as cures, any beneficial effect was

usually low; a strong placebo effect often occurs; and more research (especially in the form of

large, carefully designed clinical trials) is needed in order to draw firmer conclusions.

Some other areas of interest to researchers on probiotics are

• What is going on at the molecular level with the bacteria themselves and how they may

interact with the body (such as the gut and its bacteria) to prevent and treat diseases.

Advances in technology and medicine are making it possible to study these areas much

better than in the past.

• Issues of quality. For example, what happens when probiotic bacteria are treated or are

added to foods—is their ability to survive, grow, and have a therapeutic effect altered?

NCCAM-3

• The best ways to administer probiotics for therapeutic purposes, as well as the best doses

and schedules.

• Probiotics’ potential to help with the problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the gut.

• Whether they can prevent unfriendly bacteria from getting through the skin or mucous

membranes and traveling through the body (e.g., which can happen with burns, shock,

trauma, or suppressed immunity).

Side Effects and Risks

Some live microorganisms have a long history of use as probiotics without causing illness in

people. Probiotics’ safety has not been thoroughly studied scientifically, however. More

information is especially needed on how safe they are for young children, elderly people, and

people with compromised immune systems.

Probiotics’ side effects, if they occur, tend to be mild and digestive (such as gas or bloating).

More serious effects have been seen in some people. Probiotics might theoretically cause

infections that need to be treated with antibiotics, especially in people with underlying health

conditions. They could also cause unhealthy metabolic activities, too much stimulation of the

immune system, or gene transfer (insertion of genetic material into a cell).

Probiotic products taken by mouth as a dietary supplement are manufactured and regulated as

foods, not drugs.

Some Other Points To Consider

• If you are thinking about using a probiotic product as CAM, consult your health care

provider first. No CAM therapy should be used in place of conventional medical care or to

delay seeking that care.

• Effects from one species or strain of probiotics do not necessarily hold true for others, or

even for different preparations of the same species or strain.

• If you use a probiotic product and experience an effect that concerns you, contact your

health care provider.

• You can locate research reports in peer-reviewed journals on probiotics’ effectiveness and

safety through the resources PubMed and CAM on PubMed.

NCCAM-Sponsored Research on Probiotics

Among recent NCCAM-sponsored research are the following projects:

• Investigators at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine are

studying the effectiveness of selected probiotic agents to treat diarrhea in undernourished

children in a developing country.

NCCAM-4

• At the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, researchers have been examining probiotics for

possibly decreasing the levels of certain substances in the urine that can cause problems

such as kidney stones.

• A team at Tufts-New England Medical Center is studying probiotics for treating an

antibiotic-resistant type of bacteria that causes severe infections in people who are

hospitalized, live in nursing homes, or have weakened immune systems.

References

Sources are primarily recent reviews on the general topic of probiotics in the peer-reviewed

medical and scientific literature in English in the PubMed database, selected evidence-based

databases, and Federal Government sources.

1994-2004 U.S. specialty/other supplement sales. Nutrition Business Journal. 2005. Accessed at http://www.nutritionbusiness.com

on December 7, 2006.

Alvarez-Olmos MI, Oberhelman RA. Probiotic agents and infectious diseases: a modern perspective on a traditional

therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32(11):1567-1576.

Bifidobacteria. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Web site. Accessed at http://www.naturaldatabase.com on

December 7, 2006.

Bifidus. Thomson MICROMEDEX AltMedDex System Web site. Accessed at http://www.micromedex.com on December 7, 2006.

Cabana MD, Shane AL, Chao C, et al. Probiotics in primary care pediatrics. Clinical Pediatrics. 2006;45(5):405-410.

Doron S, Gorbach SL. Probiotics: their role in the treatment and prevention of disease. Expert Review of Anti-Infective

Therapy. 2006;4(2):261-275.

Ezendam J, van Loveren H. Probiotics: immunomodulation and evaluation of safety and efficacy. Nutrition Reviews.

2006;64(1):1-14.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the

Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Working Group on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics

in Food. Accessed at http://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf on December 7, 2006.

Gill HS, Guarner F. Probiotics and human health: a clinical perspective. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2004;80(947):516-526.

Hammerman C, Bin-Nun A, Kaplan M. Safety of probiotics: comparison of two popular strains. BMJ.

2006;333(7576):1006-1008.

Huebner ES, Surawicz CM. Probiotics in the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Gastroenterology

Clinics of North America. 2006;35(2):355-365.

Lactobacillus. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Web site. Accessed at http://www.naturaldatabase.com on

December 7, 2006.

Lactobacillus. Thomson MICROMEDEX AltMedDex System Web site. Accessed at http://www.micromedex.com on

December 7, 2006.

Probiotics: Bottom Line Monograph. Natural Standard Database Web site. Accessed at http://www.naturalstandard.com on

December 7, 2006.

Reid G, Hammond JA. Probiotics: some evidence of their effectiveness. Canadian Family Physician. 2005;51:1487-1493.

Salminen SJ, Gueimonde M, Isolauri E. Probiotics that modify disease risk.Journal of Nutrition . 2005;135(5):1294-1298.

Vanderhoof JA, Young RJ. Current and potential uses of probiotics. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology.

2004;93(5 suppl 3):S33-S37.

Walker R, Buckley M. Probiotic Microbes: The Scientific Basis. Report of an American Society for Microbiology colloquium;

November 5-7, 2005; Baltimore, Maryland. American Society for Microbiology Web site. Accessed at

http://www.asm.org/academy/index.asp?bid=43351 on December 7, 2006.

NCCAM-5

----------------------- Page 6-----------------------

For More Information

NCCAM Clearinghouse

The NCCAM Clearinghouse provides information on CAM and NCCAM, including

publications and searches of Federal databases of scientific and medical literature. The

Clearinghouse does not provide medical advice, treatment recommendations, or referrals

to practitioners.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-644-6226

TTY (for deaf and hard-of-hearing callers): 1-866-464-3615

Web site: nccam.nih.gov

E-mail: info@nccam.nih.gov

PubMed®

A service of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), PubMed contains publication information

and (in most cases) brief summaries of articles from scientific and medical journals. CAM on

PubMed, developed jointly by NCCAM and NLM, is a subset of the PubMed system and focuses

on the topic of CAM.

Web site: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez

CAM on PubMed: nccam.nih.gov/camonpubmed/

Acknowledgments

NCCAM thanks the following people for their technical expertise and review of this publication:

Carol Wells, Ph.D., University of Minnesota Medical School; Richard Oberhelman, M.D., Tulane

University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine; Patricia Hibberd, M.D., Ph.D., Tufts-

New England Medical Center; Richard Walker, Ph.D., U.S. Food and Drug Administration; and

Marguerite Klein, M.S., R.D., and Jonathan (Josh) Berman, M.D., Ph.D., NCCAM.

This publication is not copyrighted and is in the public domain.

Duplication is encouraged.

NCCAM has provided this material for your information. It is not intended to substitute

for the medical expertise and advice of your primary health care provider. We encourage

you to discuss any decisions about treatment or care with your health care provider. The

mention of any product, service, or therapy is not an endorsement by NCCAM.

National Institutes of Health

???

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

D345

Created January 2007

Updated August 2008

*D345*

web site with useful, free information:

http://www.alwaysfrugal.com/

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

image of registry return receipt of letter addressed to Makati councilor J. J. Binay

No comments:

Post a Comment